Zero position

What is the Zero Position?

The critical angle between glenoid fossa and humeral head at point of relocation. In this position all the humero-scapular muscle group axes line up and lose all rotatory/transverse pull.

This was first described as the zero position by Saha in 1957 as:

“The position during elevation in coronal or sagittal plane, in fact

in any plane where there is no further rotation, no active gliding of the

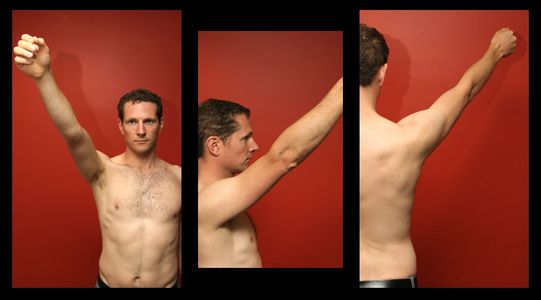

joint surfaces and circumduction; where the mechanical axis corresponds to the anatomical axis of the shaft; where gliding, rotation and "breaststroke" movements become identical is known as "zero-position." In this position the humerus is neither internally nor externally rotated. The humerus is elevated to about 165 degs. with individual variations and is in the newly acquired scapular plane.”

Milch's 4 cones of muscle

Milch had previously described the phenomena of the 4 cones of muscle lining up in 1938. In the anatomical position (noted 2 on the picture to the right) there are various translational forces acting across the joint which, when the muscles spasm, act to stop movement in a number of directions. Once the humerus is moved into an externally rotated, elevated and abducted position (zero-ish) then all of these translation forces are removed (1), the joint is in its weakest position and the humeral head has little muscular resistance stopping its return to the glenoid rim. This is also why, once the anterior capsule has been damaged, so little force is required to pop the shoulder out again, there are no counter-acting muscles stopping it from moving anteriorly.

How do I find it?

This is all about the relationship between the humeral head and the glenoid rim and absolutely nothing to do with where you, as the operator stand, or which bit of the wrist or arm you hold on to. You can have the patient supine, semi-recumbent, or hanging from their feet and still find the zero position as long as you know where the scapula is to start with. The zero position, with the scapula free to fully rotate and fully anteverted (rotated anteriorly around the chest), is found with the humerus in a forward elevation position - 165°abduction and 45°in front. With scapula fully retroverted (medial border of scapula closest to thoracic spine), it can be found with the humerus in a lateral elevation position (directly out to the side) 105°abduction and 0°in front.

Zero Position Technique

How does it work?

This technique uses a combination of scapular fixation and positioning the humerus in the “zero position.” The critical angle between glenoid fossa and humeral head at point of relocation. In this position all the humero-scapular muscle group axes line up and lose all rotatory/transverse pull - allowing the humeral head to slide back into place.

How do I know when the patient is in this position?

With the scapula free (at full rotation and anteversion) the humerus is 165°overhead and 45°in front.

Zero Position with fixed scapula

Fixing the scapula limits the rotation (around a vertical axis) and anteversion (tilting forward) that normally occurs with glenohumeral movement during abduction past 30°. The “zero position” is reached more easily, at about 105°degrees of abduction.

Cunningham Zero Position Technique

Optimal technique

I’m now going to describe the optimal single operator use of zero positioning for a patient who is co-operative and arrives in a semi-recumbent (45 degree) position on an ambulance trolley. Using the example of a left sided sub-glenoid dislocation that I’ve diagnosed based on mechanism of injury, and a large step at the acromion. (Full video of this technique below.)

1 - Analgesic position 2, rolled towel down spine, pillow behind head, operator works from side

Analgesic position 2 – move the arm to the position of most comfort for them, with a ‘hold.’ This is a firm steady axial hold (not a pull) designed to move the humeral head towards where it needs to be, taking off some of the stretch from the capsule (reducing pain), and providing confidence to the patient that you have taken control of the limb. Once you are in this position, it can be useful to ask the patient their pain level, and explain again what you are going to do.

Rolled towel and pillow – this encourages the patient to allow retroversion of scapula, and their head to relax back in a supported way. This relaxation of spine and neck muscles will facilitate subsequent shoulder muscle relaxation.

2 - Slow abduction with gentle anterior and posterior movement of the humerus

This gets the patient used to continuous slow anterior (forwards) and posterior (backwards) movement and also allows a small amount of momentum once the zero position is reached to encourage the humeral head to slide over the glenoid rim. Externally rotate to neutral, there’s nothing to be gained anatomically by forcing excessive external rotation, and you are more likely to cause pain, subsequent spasm and failure of reduction.

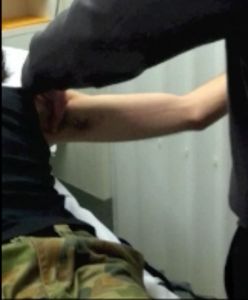

3 - Fix the humeral head with your thumb

The humeral head may be gently fixed medially/ posteriorly (inwards and backwards)

Using your thumb to stop the head from sliding around during reduction. This fixes the head against the rim providing a fulcrum for the head to move around into the glenoid fossa.

Note - do not attempt to push the head laterally, this won't work anatomically and will just hurt the patient.

4 - Reach Zero Position

Stop at 90 degrees, remind patient to relax and let you remain in control of the arm when the shoulder starts to reduce, then move the last 10-15 degrees slowly, with the forward/backward gentle continuous movement.

Scapula, don't pull, and position options

REMEMBER THE SCAPULA!

The beauty of this technique is that you have a constant reference of scapular positionfrom the patient, as long as they have the anatomical landmarks of the scapula palpable. This technique can be performed with the patient in any position (sitting, lying, hanging upside down from feet) as long as you know where the scapula is compared to the humeral head.

Be flexible, if you find that the scapula is fully anteverted then you know the “zero position” that you are aiming for is 165°overhead and 45°in front. If you can fix your scapula in retroversion then you will only need to lift the arm to approximately 100°abduction. If you feel that the scapula is winging out and the humeral head is wedged beneath the rim then you need to aim for the more anterior end point. If unsuccessful with a wedged head then move to a scapular manipulation technique if patient comfortable, or remove muscle spasm with drugs and try the zero position once patient is asleep.

DON’T PULL!

Milch’s method was described in 1949 and discussed elevating the arm “with the greatest gentleness.”That’s right – no traction. If you pull during this manoeuvre your patient will feel pain and the reflex spasm will fight against your attempted reduction.

VIDEO – click below to see video demonstration of the Zero Position Technique with explanation

Optional Positions

Below are similar descriptions of the steps for Zero positions with your patient and you in different starting positions.

Zero Position Technique – patient seated, operator behind

Analgesic position 2, rolled towel down spine, operator works from behind

Analgesic position 2 – move the arm to the position of most comfort for them, with a ‘hold.’ This is a firm steady axial hold (not a pull) designed to move the humeral head towards where it needs to be, taking off some of the stretch from the capsule (reducing pain), and providing confidence to the patient that you have taken control of the limb. Once you are in this position, it can be useful to ask the patient their pain level, and explain again what you are going to do.

Sit your patient in a hard backed chair (with no wheels), stand behind the affected limb. Place your left hand over the trapezius and spine of scapula - this fixes the scapula and informs you of any scapular movement during the procedure.

Rolled towel behind spine optional, may assist some patients to sit up, relax and retract their shoulders. Relax spine and neck muscles with a pillow behind them if more comfortable, encourage scapular retroversion if they are able.

2 – Slow abduction and external rotation, add gentle anterior and posterior movement of the humerus

This gets the patient used to continuous slow anterior (forwards) and posterior (backwards) of the humerus and also allows a small amount of momentum once the zero position is reached to encourage the humeral head to slide over the glenoid rim. Externally rotate to neutral, there’s nothing to be gained anatomically by forcing excessive external rotation, and you are more likely to cause pain, subsequent spasm and failure of reduction.

3 - Fix the humeral head with a thumb

The humeral head may be gently fixed medially/ posteriorly (inwards and backwards)

Use an assistant’s thumb to stop the head from sliding around during reduction. This fixes the head against the rim providing a fulcrum for the head to move around into the glenoid fossa.

4 - Reach Zero Position

Stop at 90 degrees abduction, remind patient to relax and let you remain in control of the arm when the shoulder starts to reduce, then move the last 10-15 degrees slowly, with the forward/backward gentle continuous movement.

Zero Position Technique – patient seated, operator in front

1 - Analgesic position 2, rolled towel down spine, operator works from behind

Analgesic position 2 – move the arm to the position of most comfort for them, with a ‘hold.’ This is a firm steady axial hold (not a pull) designed to move the humeral head towards where it needs to be, taking off some of the stretch from the capsule (reducing pain), and providing confidence to the patient that you have taken control of the limb. Once you are in this position, it can be useful to ask the patient their pain level, and explain again what you are going to do.

Sit your patient in a hard backed chair (with no wheels), stand behind the affected limb. Place your left hand over the trapezius and spine of scapula - this fixes the scapula and informs you of any scapular movement during the procedure.

Rolled towel behind spine optional, may assist some patients to sit up, relax and retract their shoulders. Relax spine and neck muscles with a pillow behind them if more comfortable, encourage scapular retroversion if they are able.

2 – Slow abduction and external rotation, add gentle anterior and posterior movement of the humerus

This gets the patient used to continuous slow anterior (forwards) and posterior (backwards) movement of the humerus and also allows a small amount of momentum once the zero position is reached to encourage the humeral head to slide over the glenoid rim. Externally rotate to neutral, there’s nothing to be gained anatomically by forcing excessive external rotation, and you are more likely to cause pain, subsequent spasm and failure of reduction.

3 – Fix the humeral head with a thumb

The humeral head may be gently fixed medially/ posteriorly (inwards and backwards)

Use your thumb to stop the head from sliding around during reduction. This fixes the head against the rim providing a fulcrum for the head to move around into the glenoid fossa.

4 – Reach Zero Position

Stop at 90 degrees abduction, remind patient to relax and let you remain in control of the arm when the shoulder starts to reduce, then move the last 10-15 degrees slowly, with the forward/backward gentle continuous movement. If the patient has anteverted their scapula then it will be difficult to get them to a 165/45 position with you standing in front. You will have to be flexible and walk around the limb at this point.

Zero Position Technique – patient lying, operator at side

1 - Analgesic position 2, rolled towel down spine, operator works from side

Analgesic position 2 – move the arm to the position of most comfort for them, with a ‘hold.’ This is a firm steady axial hold (not a pull) designed to move the humeral head towards where it needs to be, taking off some of the stretch from the capsule (reducing pain), and providing confidence to the patient that you have taken control of the limb. Once you are in this position, it can be useful to ask the patient their pain level, and explain again what you are going to do.

Your patient is lying down, so make sure you keep a 360 degree ‘big picture’ view of where the scapula is, and don’t slide them off the bed! You won’t have your hands on the scapula, but can use an assistant to feel it, or push it medially if it is “winging” with the tip sticking out laterally – you will also then need to aim for a 165/45 position.

Rolled towel behind spine optional, may assist some patients to retract their shoulders. Relax spine and neck muscles with a pillow behind them if more comfortable, encourage scapular retroversion if they are able.

2 - Slow abduction and external rotation, add gentle anterior and posterior movement of the humerus.

This gets the patient used to continuous slow anterior (forwards) and posterior (backwards) movement of the humerus and also allows a small amount of momentum once the zero position is reached to encourage the humeral head to slide over the glenoid rim. Externally rotate to neutral, there’s nothing to be gained anatomically by forcing excessive external rotation, and you are more likely to cause pain, subsequent spasm and failure of reduction.

3 – Fix the humeral head with a thumb

Moving around the patient’s arm and holding the wrist of the affected limb with one hand, and using your thumb to fix the humeral head with the other. The humeral head is gently fixed medially/ posteriorly (inwards and backwards) to stop the head from sliding around during reduction. This fixes the head against the rim providing a fulcrum for the head to move around into the glenoid fossa.

4 – Reach Zero Position

Stop at 90 degrees abduction, remind patient to relax and let you remain in control of the arm when the shoulder starts to reduce, then move the last 10-15 degrees slowly, with the forward/backward gentle continuous movement. If the scapula has rotated around to an anteverted position you will need to aim more for a 165/45 end position.

Other zero position techniques

What other techniques use the Zero Position?

Many techniques end up in the Zero Position without specifically referring to it as such, often focusing on where to stand, and how to position the patient. Not to criticise any of these methods (other than those that add traction for no apparent anatomical reason) but it is important to fully understand the important relationship between the dislocated humerus and glenoid for when your ‘go to’ technique doesn’t work. These techniques include Milch, Fares, Spaso, Janecki, and the Eskimo technique.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.