Shoulder Anatomy - Anterior Dislocation

Anatomy in dislocation

An understanding of the anatomy of the shoulder in dislocation is essential when attempting reduction.

The position of the glenoid rim of the scapula in relation to the humeral head is the key to a successful reduction, unintentional movement of one of these components during a manoeuvre will often determine success or failure.

A good clinical examination before attempted reduction and, if necessary, an assistant fixing the scapula will help you assess and reduce the dislocation quickly and easily. The size of the acromial step and palpable humeral head, and the ability to adduct may help you distinguish between the sub-coracoid (small step, higher/harder to palpate humeral head, can adduct dependent on spasm) and sub-glenoid (large step, lower head, more likely to be wedged in abduction) subtypes.

Click here for a video showing the movements of the humeral head and scapular during dislocation and reduction. This shows adduction of humerus, external rotation of humeral head and retroversion of the scapula with subsequent reduction from subcoracoid and subglenoid positions.

Anatomy in a dislocated joint

What changes when the humeral head moves out of the glenoid fossa?

In a dislocation the anatomy and inherent stability of the joint changes.

The humeral head sits in either a subcoracoid or subglenoid position.

To relocate the humeral head needs to move anteriorly and laterally (from subcoracoid) or supralaterally (from subglenoid).

What is stopping the humeral head from reducing?

The return of the humeral head to the glenoid fossa is confronted by two major obstacles – static and dynamic forces.

Static and Dynamic Forces

Static forces

A fixed obstacle (the prominent anteriorly placed glenoid rim/labrum) sits supralateral to the displaced head - relocation requires the humeral head to move anterior and lateral/supralateral.

Remember the scapula – the position of the glenoid fossa is often forgotten during reduction attempts.

If the scapula is fully migrated around the chest wall you will struggle to reduce the shoulder even if you are doing everything else correctly.

Q – How is this obstacle overcome?

A – This can occur in 2 ways:

1 - External rotation of the humeral head which presents a greater articular surface superiorly to the receiving fossa allowing it to roll past the rim.

2 - Rotation of the scapula with retroversion which presents an easier path for the returning head.

Dynamic forces

The dynamic stabilisers normally hold the joint in place (pulling the humerus medially) but in a dislocation muscular spasm continues to pull on the humeral head and shaft.

Q – Which muscles are causing the problem?

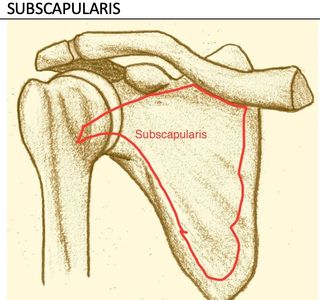

A - The long head of biceps and the subscapularis muscle have long been thought to play major roles in resisting reduction of the displaced humeral head.

The long head of biceps is positioned longitudinally across the glenohumeral joint and acts to pull the dislocated humeral head upwards, fixing it in the subcoracoid/glenoid area. In spasm, this muscle resists anterior movement of the head and may also bowstring anterolateral to the axis of the head, further restricting the returning humeral head.

Subscapularis inserts into the lesser tuberosity, internally rotating the humerus (resisting external rotation) and holding the head medially (resisting lateral movement).

Inertia and articular slippiness

You may find that you have the humeral head/ glenoid rim interface perfectly positioned but nothing happens, even with the muscles fully relaxed. Even though the humeral head ‘wants’ to return to the rim there may be an inertia of movement that needs to be overcome. Overcoming this inertia can be helped by using the fact that the humeral head and the glenoid rim are in opposition and, being articular surfaces, are slippery. Therefore, producing a small amount of momentum by gently moving the humerus anteriorly/ posteriorly can cause these surfaces to slide against each other, facilitating reduction.

It's not magic, it's anatomy

Be sceptical!

I recently presented a dislocation workshop in the beautiful Mediterranean town of Antalya, Turkey. I was sat with my friend Basak Yilmaz (below pic) and we were joined by a Slovenian emergency doc called Gregor who admitted to being sceptical about the techniques prior to the session having previously seen a couple of videos on youtube. Then, after I had spent the first 30 minutes of the session talking about the anatomy of the shoulder joint, in and out of the dislocated position, the underlying process of the techniques made sense to him. I think anatomy is fundamental to understanding what is likely to work on your patient, and what isn’t.

Twitter @drncunningham

This led onto a longer discussion with my fellow sceptic Gregor about the need for depth of medical education in the age of FOAMed, twitter, and how to filter the vast amount of education available. I lost the Twitter argument, Basak @basakED signed me up, and Gregor @gregorprosen is my first official Twitter friend.

Basic shoulder anatomy

Basic Shoulder Anatomy

Check out this great summary of shoulder anatomy by orthopaedic surgeon Randale C. Sechrest MD. Click button below for this 7 minute video covers basic anatomy with some great graphics.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.