Posterior shoulder dislocation

Anatomy - Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

An understanding of the anatomy of the shoulder in dislocation is essential when attempting reduction. The position of the glenoid rim of the scapula in relation to the humeral head is the key to a successful reduction, unintentional movement of one of these components during a manoeuvre will often determine success or failure. The humeral head needs to move anteriorly, medially and superiorly in order to return to the glenoid fossa.

Clinical Presentation

A good clinical examination before attempted reduction. In a posterior dislocation there may be little or no obvious acromial step and the humeral head may be hard to palpate - there may be a palpable depression at the anterior deltoid. The patient is usually holding the humerus in adduction and internal rotation, and will not be able to externally rotate the humerus without discomfort.

Other injuries

Proximal humeral fractures include anatomical neck and lesser tuberosity of the humerus.

Reverse Hill-Sachs lesion seen here (left) on an Xray from a patient who had sustained a posterior dislocation following a seizure. Also called a McLaughlin lesion, this is an impact fracture of the postero-medial humeral head.

Reverse Bankart's lesion - this is a detachment of the postero-inferior labrum. You may see a bony fragment avulsed on Xray, but an MRI will pick up this lesion best.

Glenohumeral ligament avulsion which may contribute to future instability.

POLPSA (posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsion) lesion can occur with a posterior dislocation - damage to the periosteum of the scapula and posterior glenoid labrum. Again, best seen on MRI.

Imaging

AP and lateral views

The humeral head sits posterior to the glenoid rim, twisting slightly into internal rotation with a resultant “lightbulb” sign seen on X-Ray in the AP view. A “reverse Hills-Sachs”/McLaughlin lesion may also be seen, this is an impact fracture of the anteromedial humeral head. The posterior dislocation can be missed on X-ray, so think about it if you have a patient reluctant to externally rotate their humerus, especially if confused or post-ictal. CT scan if X-Ray unclear or if you can’t get a decent axial view.

Normal view in internal rotation

Taking just an AP X-ray can mean missing a posterior dislocation in up to 50% of cases. The normal

Technique

Theory

This technique is something of a ‘reverse Kocher’s’ and uses a combination of:

- Voluntary retraction of scapula, reducing the fixed obstruction of the lateral aspect of the glenoid rim to the returning humeral head, combined with a hold to take over control of the upper arm

1 - Internal rotation and adduction to reduce wedging behind rim and to lever the head laterally, optimising the position of the humeral head

2 - elevation of the humerus which then lifts the head up onto the rim

3 - Finally external rotation of the humerus, this apposes the articular surface of the humeral head to the rim, releasing the tension of the capsule and allowing the head to slide into place

Step-by-step

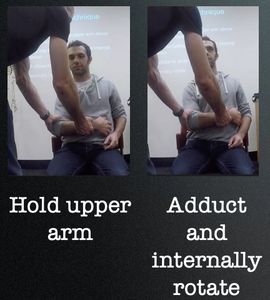

Firmly and gently hold upper arm (above elbow) and forearm

1 - Place into further adduction and internal rotation

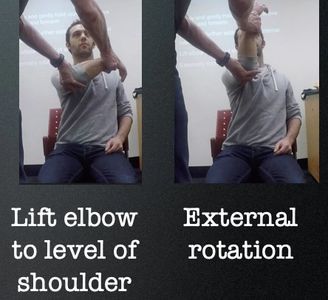

2 - Lift elbow to level of shoulder

3 - Externally rotate

Note - if the scapula starts to protract (rotate forwards around chest wall) then you will need to move the elbow slightly across the front of the torso in order to maintain adduction and keep the head at the posterior glenoid rim. If you don't do this, it will stay wedged behind the rim.

The humeral head may reduce during manoeuvres 1,2 or3

How-to video

Click here for a step-by-step explanation of the technique (thanks to Dr Matthew Kilmurray).

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.